James Madison, the fourth President of the United States, served from 1809 to 1817, a period marked by significant challenges and substantial achievements. His presidency is most famously associated with the War of 1812, often called “America’s Second War of Independence.” This conflict was both a test of the young nation’s resilience and a defining moment in Madison’s leadership. The War of 1812 was a complex event that arose from a series of international tensions, domestic pressures, and ideological commitments. This article will explore the challenges Madison faced during the war, the strategies he employed to navigate them, and the lasting achievements that emerged from his presidency.

The Road to War: Preceding Challenges

James Madison’s presidency began under the shadow of escalating tensions with Great Britain and France. These tensions stemmed from the broader Napoleonic Wars in Europe, which engulfed much of the Western world. The United States, attempting to maintain its neutrality, found itself caught between the aggressive policies of the two European powers.

One of the most significant challenges Madison inherited was the issue of British impressment. The British Royal Navy, desperately needing manpower for its war against Napoleon, routinely seized American sailors and forced them into service. This practice was viewed as a direct affront to American sovereignty and stoked widespread anger across the United States. Additionally, Britain’s Orders in Council, which imposed trade restrictions on neutral countries trading with France, severely disrupted American commerce.

On the domestic front, the United States was also grappling with political divisions. The Federalist Party, particularly strong in New England, was staunchly opposed to the idea of war with Britain, viewing it as disastrous for American trade. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Madison, was more inclined toward confrontation, driven by a sense of national honor and the need to protect American interests. The country was also dealing with ongoing conflicts with Native American tribes in the Northwest Territory, which were often exacerbated by British support for the tribes as a means of countering American expansion.

In this volatile environment, Madison sought to use economic measures to coerce Britain and France into respecting American neutrality. The Embargo Act of 1807, passed under Madison’s predecessor Thomas Jefferson, had proven to be an economic failure and deeply unpopular. In an attempt to find a middle ground, Madison implemented the Non-Intercourse Act and later Macon’s Bill No. 2, which aimed to restore trade while still applying pressure on Britain and France. However, these measures did little to change British policy, and tensions continued to rise.

Declaring War: A Difficult Decision

By 1812, Madison faced mounting pressure from the “War Hawks,” a group of young, aggressive congressmen led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. These leaders advocated for war as a means of defending American honor, protecting frontier settlements, and possibly expanding U.S. territory into Canada. The War Hawks argued that only through war could the United States assert itself as a sovereign nation and secure its rights on the global stage.

On June 1, 1812, after much deliberation, Madison sent a war message to Congress, outlining the various grievances against Britain, including impressment, interference with American trade, and incitement of Native American attacks on American settlers. Congress, after a heated debate, declared war on June 18, 1812, marking the beginning of the War of 1812.

The decision to go to war was not universally popular. In New England, where the Federalist Party was strongest, opposition to the war was fierce. Many in the region saw the conflict as unnecessary and economically ruinous, given the region’s reliance on maritime trade. The war would come to be known as “Mr. Madison’s War” by its detractors, reflecting the deep divisions it caused within the country.

The War of 1812: Challenges on the Battlefield

The early years of the War of 1812 were marked by a series of military failures and challenges for Madison’s administration. The U.S. military was ill-prepared for war, suffering from a lack of funding, inadequate training, and poor leadership. The regular army was small and scattered, and the militia forces, which were relied upon heavily, were often undisciplined and uncooperative.

One of Madison’s key challenges was the failed invasions of Canada. The initial American strategy aimed to strike at British forces in Canada, hoping that a successful invasion would force Britain to negotiate. However, these efforts ended in disaster. In 1812, General William Hull’s invasion of Upper Canada ended with his surrender at Detroit, a humiliating defeat for the United States. Subsequent attempts to invade Canada in 1813 and 1814 also met with limited success, as American forces were repeatedly repelled by well-entrenched British and Canadian forces.

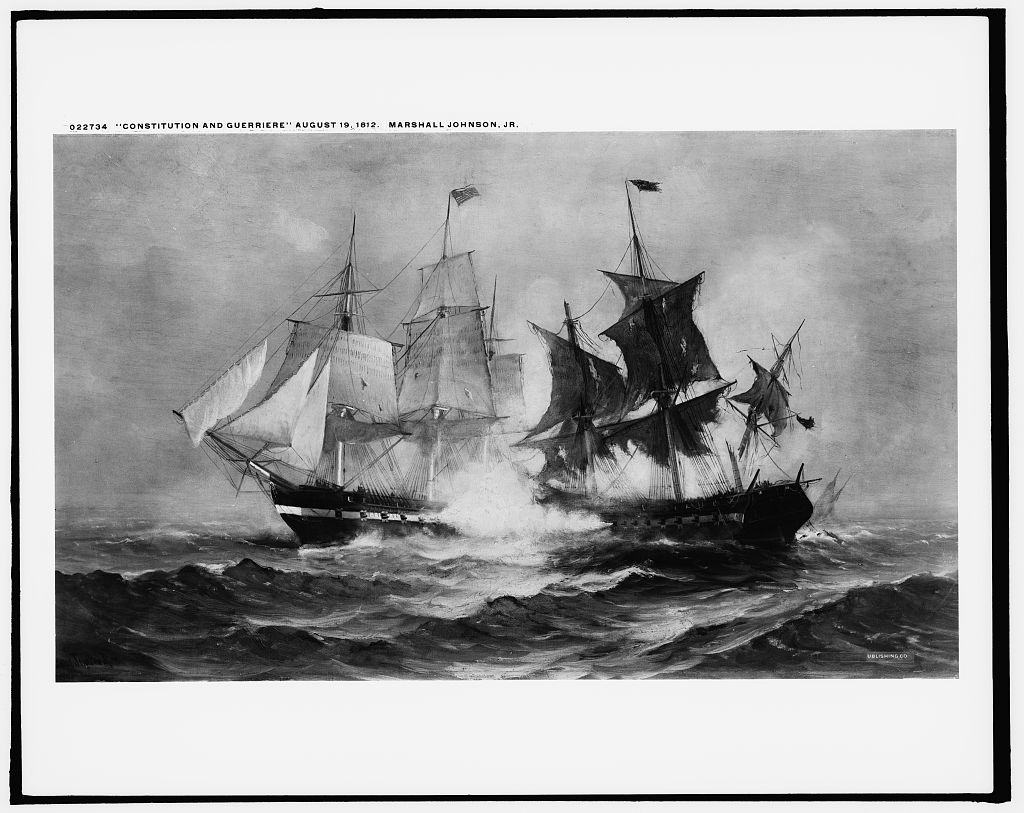

Meanwhile, on the high seas, the U.S. Navy, though small, managed to achieve some notable victories. American frigates like the USS Constitution won several engagements against British ships, providing a much-needed morale boost and demonstrating that the United States could hold its own in naval combat. However, the British naval blockade of American ports severely disrupted trade and weakened the U.S. economy, creating additional pressure on Madison’s administration.

Perhaps the greatest challenge Madison faced during the war came in 1814, when British forces launched a major offensive after Napoleon’s defeat in Europe allowed Britain to divert more resources to the American conflict. In August 1814, British troops captured Washington, D.C., and set fire to several public buildings, including the White House and the Capitol. This event was a significant psychological blow to the nation and to Madison personally, as he was forced to flee the capital. Despite this setback, Madison remained resolute, and the burning of Washington galvanized American resistance.

Turning the Tide: Key Achievements

Despite the numerous challenges, Madison’s presidency during the War of 1812 was also marked by significant achievements that ultimately shaped the future of the United States.

One of the most critical turning points in the war came with the American victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in September 1813, under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry. This victory secured control of the Great Lakes and paved the way for General William Henry Harrison’s triumph at the Battle of the Thames, where the influential Native American leader Tecumseh was killed. These victories weakened the British and Native American alliance in the Northwest and helped secure the American frontier.

Another crucial achievement was the defense of Baltimore in September 1814. After their success in Washington, British forces turned their attention to Baltimore, a major port city. However, the city’s defenses, including the stronghold at Fort McHenry, successfully repelled the British attack. The sight of the American flag still flying over Fort McHenry the morning after the bombardment inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which would later become the national anthem.

The final major victory came at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815, where General Andrew Jackson led a diverse force of regulars, militia, free African Americans, and even pirates to a decisive victory against a much larger British force. Although the battle took place after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed, ending the war, the victory at New Orleans became a symbol of American resilience and fighting spirit.

The Treaty of Ghent: Diplomatic Success

The Treaty of Ghent, signed on December 24, 1814, officially ended the War of 1812. Negotiated in the Belgian city of Ghent, the treaty was largely a return to the status quo ante bellum, meaning that neither side gained or lost significant territory. The issues of impressment and neutral rights, which had been central to the war, were not addressed in the treaty, largely because the defeat of Napoleon had made them moot.

Despite the treaty’s lack of decisive terms, the end of the war was viewed as a success for the United States. The fact that the young nation had managed to hold its own against the world’s preeminent military power was seen as a validation of American independence and sovereignty. Madison’s leadership during the war, despite the numerous setbacks, was credited with preserving the nation and ultimately leading it to a favorable outcome.

The Legacy of Madison’s War Presidency

The War of 1812 had a profound impact on the United States and on Madison’s legacy as president. Although the war exposed significant weaknesses in the American military and economy, it also led to important developments that would shape the nation’s future.

One of the most significant outcomes of the war was the surge of nationalism it inspired. The victories at Baltimore and New Orleans, in particular, fostered a sense of national pride and unity. This newfound sense of American identity contributed to what is often called the “Era of Good Feelings,” a period of political harmony and national optimism that followed the war.

The war also had important economic consequences. The British blockade had forced the United States to become more self-sufficient, leading to the growth of American manufacturing. This shift laid the groundwork for the country’s eventual industrialization. Additionally, the war highlighted the need for improved infrastructure, leading to a renewed focus on internal improvements such as roads and canals.

Politically, the war marked the decline of the Federalist Party, which had vehemently opposed the conflict. The party’s anti-war stance, particularly in New England, where some Federalists even considered secession, led to its marginalization in national politics. By the end of Madison’s presidency, the Federalist Party was effectively dead, paving the way for the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party.

Madison’s handling of the War of 1812 also helped to solidify the role of the presidency in wartime leadership. His decision-making, particularly his insistence on civilian control of the military and his efforts to balance military needs with respect for civil liberties, set important precedents for future presidents.