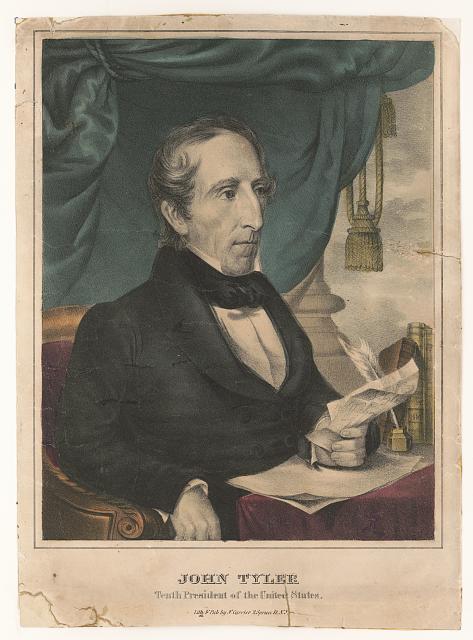

John Tyler, the 10th President of the United States, holds a unique place in American history as the first Vice President to ascend to the presidency upon the death of his predecessor. Tyler’s unexpected rise to power in 1841 set a critical precedent for the line of presidential succession, shaping the office of the presidency and the broader political landscape of the United States. His tenure was marked by significant challenges and controversies, including his battle with Congress, his break from the Whig Party, and his role in the annexation of Texas. This article explores how John Tyler became president, the controversies that defined his administration, and the lasting historical impact of his presidency.

The Unexpected Ascension: How John Tyler Became President

John Tyler’s rise to the presidency was unprecedented and unforeseen. He was elected Vice President in 1840 on the Whig Party ticket alongside William Henry Harrison. The campaign was famously known for its slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” highlighting Harrison’s military heroics and Tyler’s role as his running mate. However, Tyler was not a central figure in the campaign and was seen primarily as a means to balance the ticket, given his Southern background and states’ rights beliefs.

On March 4, 1841, William Henry Harrison was inaugurated as the 9th President of the United States. Unfortunately, Harrison, who delivered the longest inaugural address in history in inclement weather, caught a cold that developed into pneumonia. Just 31 days into his term, Harrison died on April 4, 1841, making him the first U.S. president to die in office.

Harrison’s sudden death created a constitutional crisis, as the U.S. Constitution was ambiguous about what should happen when a president died in office. The Constitution stated that the “Powers and Duties” of the presidency would “devolve on the Vice President” in such a scenario, but it was unclear whether the Vice President would become the full president or merely act as one until a new election could be held.

John Tyler quickly moved to assert his position, declaring himself the full President of the United States rather than merely an acting president. He took the presidential oath of office, establishing a critical precedent that has been followed ever since. Despite opposition from some members of Congress, who referred to him as “His Accidency,” Tyler firmly established the principle that the Vice President would fully assume the presidency in the event of the president’s death, setting a lasting precedent for presidential succession.

The Challenges of the Tyler Presidency

John Tyler’s presidency was fraught with challenges from the outset. As a former Democrat who had switched to the Whig Party due to his opposition to Andrew Jackson’s policies, Tyler was viewed with suspicion by both parties. His ideological commitment to states’ rights and limited federal government often put him at odds with the core policies of the Whig Party, particularly those championed by Henry Clay, the powerful Whig leader in Congress.

The most significant conflict between Tyler and the Whigs revolved around the issue of the national bank. The Whigs, led by Clay, sought to reestablish a national bank after Jackson had dismantled the Second Bank of the United States. However, Tyler, adhering to his strict interpretation of the Constitution and his belief in states’ rights, vetoed two bills aimed at creating a new national bank.

Tyler’s vetoes infuriated the Whigs, leading to a dramatic break between the President and his party. All but one member of Tyler’s cabinet, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, resigned in protest. The Whigs officially expelled Tyler from the party, leaving him politically isolated and without a strong base of support in Congress.

This break with the Whigs had profound implications for Tyler’s presidency. With no party backing him, Tyler struggled to advance his legislative agenda and faced repeated opposition from Congress. Despite these challenges, Tyler remained resolute in his principles, frequently using his veto power to block legislation he deemed unconstitutional or harmful to the interests of the states.

Foreign Policy Successes and the Annexation of Texas

Although Tyler faced significant domestic challenges, his presidency is perhaps best remembered for its achievements in foreign policy, particularly the annexation of Texas. Tyler was a strong advocate for the expansion of U.S. territory, a belief that aligned with the growing sentiment of Manifest Destiny—the idea that the United States was destined to expand across the North American continent.

The Republic of Texas had won its independence from Mexico in 1836, but its status as an independent nation was precarious. Texas sought annexation by the United States, but the issue was highly contentious, with debates centered around the expansion of slavery and the potential for conflict with Mexico.

Tyler saw the annexation of Texas as a way to secure American interests and expand the nation’s territory. However, his efforts were initially stymied by the Senate, where opposition from anti-slavery Northerners and Whigs blocked an annexation treaty in 1844. Undeterred, Tyler pursued an alternative route, using a joint resolution of Congress to achieve annexation. This approach required only a simple majority in both houses of Congress, rather than the two-thirds majority needed for a treaty.

In the final days of his presidency, Tyler succeeded in securing the passage of the joint resolution, and Texas was formally offered statehood. Although Texas would not officially become a state until December 1845, after Tyler had left office, his role in facilitating its annexation was a significant achievement that expanded U.S. territory and set the stage for further westward expansion.

The Tyler Precedent: Legacy and Historical Impact

John Tyler’s presidency is often remembered more for the precedents it set than for its legislative achievements. His firm assertion of the right to fully assume the presidency upon the death of a sitting president established a critical constitutional precedent that has endured to this day. This “Tyler Precedent” was later codified in the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1967, which clearly outlines the line of presidential succession and the process for filling a vacancy in the vice presidency.

Tyler’s presidency also highlighted the challenges of governing without strong party support, a situation that has been rare in American history but instructive for understanding the importance of party politics in the U.S. political system. His use of the veto power, often in opposition to the will of Congress, underscored the potential for conflict between the executive and legislative branches, a theme that would recur throughout American history.

Despite these significant contributions to the development of the American presidency, Tyler’s legacy is complicated by his later actions. After leaving office, Tyler returned to his plantation in Virginia and became increasingly aligned with Southern interests. In the lead-up to the Civil War, Tyler played a prominent role in efforts to preserve slavery and later became a member of the Confederate Congress—the only former U.S. president to do so. This association with the Confederacy has tarnished Tyler’s legacy, casting a shadow over his earlier achievements.