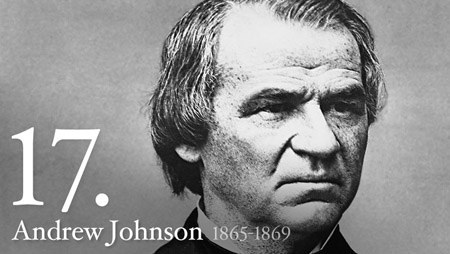

Andrew Johnson, the 17th President of the United States, served from April 15, 1865, to March 4, 1869. His presidency, which followed the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was marked by significant challenges, including the reconstruction of the Southern states, political conflicts with Congress, and the first impeachment of a U.S. president. This article provides a detailed timeline of Johnson’s presidency, highlighting key dates and events that defined his time in office.

Ascension to the Presidency: April 1865

- April 15, 1865: Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson is sworn in as the 17th President of the United States. Johnson, a Southern Democrat and former Vice President, inherits the presidency at a critical juncture in American history.

Early Reconstruction Efforts: 1865

- May 29, 1865: Johnson issues two proclamations: one grants amnesty to most former Confederates who take an oath of allegiance to the Union, and the other outlines the process for Southern states to reestablish their governments and regain representation in Congress. These policies, known as Presidential Reconstruction, are lenient towards the South and do not include protections for newly freed African Americans.

- Summer 1865: Southern states begin to implement “Black Codes,” restrictive laws aimed at controlling the labor and behavior of former slaves. These codes alarm Northern Republicans and highlight the inadequacies of Johnson’s Reconstruction policies.

Conflict with Congress: 1866

- February 1866: Johnson vetoes the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, which aimed to extend the life and powers of the Freedmen’s Bureau, an agency established to assist former slaves. Congress overrides his veto, marking the beginning of a power struggle between Johnson and the Republican-dominated Congress.

- April 1866: Congress passes the Civil Rights Act of 1866, granting citizenship and equal rights to all persons born in the United States, except Native Americans. Johnson vetoes the bill, but Congress overrides the veto, enacting the first major piece of civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

- June 1866: Congress passes the 14th Amendment, which grants citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and guarantees equal protection under the law. Johnson opposes the amendment, further straining his relationship with Congress.

Radical Reconstruction: 1867

- March 2, 1867: Congress passes the Reconstruction Acts, dividing the South into five military districts and requiring Southern states to draft new constitutions guaranteeing black male suffrage as a condition for reentry into the Union. Johnson vetoes the acts, but Congress overrides his vetoes, marking the beginning of Radical Reconstruction.

- August 1867: Johnson attempts to remove Edwin M. Stanton, a Radical Republican, from his position as Secretary of War. Johnson’s defiance of the Tenure of Office Act, which requires Senate approval for the removal of certain officeholders, sets the stage for his impeachment.

Impeachment and Political Struggles: 1868

- February 24, 1868: The House of Representatives votes to impeach Andrew Johnson, charging him with high crimes and misdemeanors for violating the Tenure of Office Act and other alleged abuses of power. Johnson becomes the first U.S. president to be impeached.

- March-May 1868: Johnson’s impeachment trial takes place in the Senate. The trial concludes with Johnson’s acquittal on May 16, 1868, as the Senate falls one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed to convict him. Johnson remains in office but is politically weakened.

Final Year and Legacy: 1868-1869

- July 1868: The 14th Amendment is ratified, granting citizenship and equal protection to all persons born or naturalized in the United States. Johnson’s opposition to the amendment underscores his contentious relationship with Congress and the Radical Republicans.

- November 1868: Ulysses S. Grant, a Republican and former Union general, is elected President of the United States, signaling a shift in political power and the end of Johnson’s presidency.

- March 4, 1869: Andrew Johnson’s presidency officially ends as Ulysses S. Grant is inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States. Johnson leaves office with a tarnished legacy, having failed to effectively manage Reconstruction and having been impeached by Congress.

Post-Presidency and Legacy

- 1875: Johnson returns to politics and is elected to the U.S. Senate from Tennessee. He serves for a few months before his death on July 31, 1875.

Legacy and Impact

Andrew Johnson’s presidency is marked by significant controversies and challenges:

- Reconstruction Policies: Johnson’s lenient approach to Reconstruction and his opposition to civil rights legislation for African Americans led to significant conflict with Congress and hindered efforts to achieve racial equality in the South.

- Impeachment: Johnson’s impeachment highlights the intense political struggles of his presidency and sets a precedent for the limits of presidential power.

- Relationship with Congress: Johnson’s contentious relationship with Congress and his frequent vetoes illustrate the deep divisions between the executive and legislative branches during his presidency.

Conclusion

Andrew Johnson’s presidency, though brief and tumultuous, played a crucial role in shaping the course of Reconstruction and the post-Civil War era in the United States. His lenient policies towards the South, opposition to civil rights legislation, and impeachment by Congress highlight the significant challenges and controversies of his time in office. Despite his efforts to restore the Union and heal the nation’s wounds, Johnson’s presidency is often remembered for its failures and the enduring impact of his contentious relationship with Congress.